Mastering both the pen and the sword? Cicero in the game of Diplomacy

A commentary on Meta's AI performance and what it means for further AI applications to wargaming

“Diplomacy without arms is like music without instruments.” - Frederick II

I was recently asked about Cicero’s feat in the game of Diplomacy, and what it meant for the future use of AI in bespoke wargames. Diplomacy being one of my very favourite games, my answer was lengthy enough to justify writing a piece about it, so here we are.

In this analysis, I attempt to measure how strong Cicero really is, identify what enabled such a level of performance, and suggest some ways in which such an AI could be used in professional wargaming.

Long story short: No, fortunately, Cicero is not a mischievous and treacherous machine that manipulates its poor human adversaries to lead them to their inevitable downfall. Actually, it is even impressively honest and makes for a pretty reliable ally. Its success comes from its incredibly strong tactical skills (in a similar fashion to other AIs in 2 players games such as chess, go, starcraft etc), while it is just ‘good enough’ in the social aspect of the game so as not to suffer too much from its limited communication abilities. Yet, the way it successfully imitates the communication style of strong human players and cooperates with them opens up promising paths for the use of AI in bespoke multiplayer wargames. In particular, its use of implicit signaling is extremely impressive and might constitute the main takeaway from Cicero’s experiment from a strategic point of view.

Diplomacy and the Cicero experiment

To start off, what is Diplomacy, and what is Cicero?

Famous for how effective it is at breaking friendships, Diplomacy is a commercial wargame published by Allan B. Calhamer in 1959 revolving around the notion of balance of power. Seven players compete and cooperate to reach hegemony on the continent or, at least, to achieve survival. Each turn is simultaneous and players need to coordinate their actions to progress at all. This, combined with the quick creation of a check and balance system in a ‘winner takes all’ setting, makes good and active diplomacy paramount in order to achieve success, hence the name of the game.

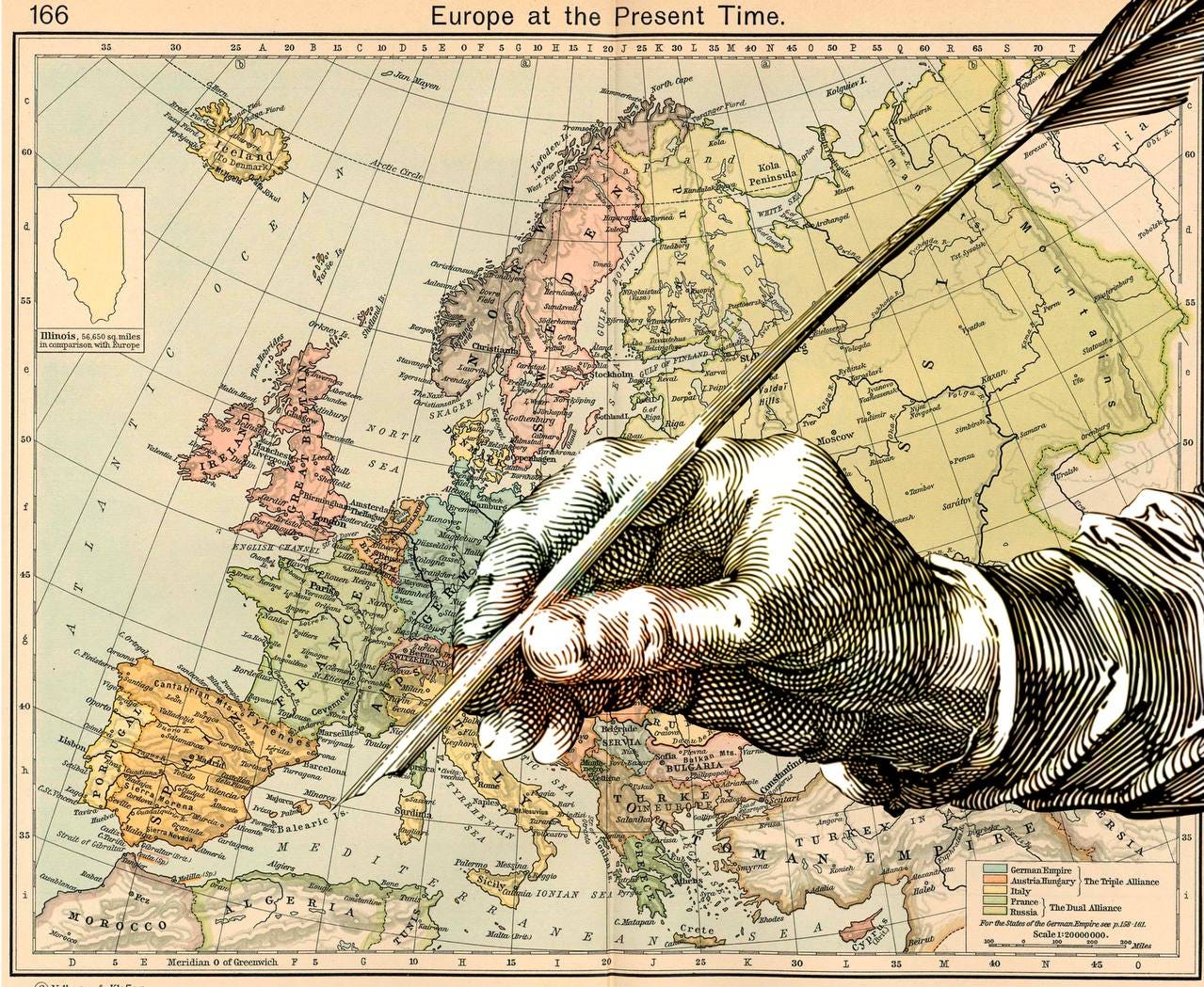

The map at the start of the gameCicero is an AI designed by Meta Fundamental AI Research Diplomacy Team to play this game. In December 2022, they published a paper presenting their experiment and findings: across 40 games of an anonymous online Diplomacy league (the BlitzCon Diplomacy Tournament), Cicero achieved more than double the average score of the human players and ranked in the top 10% of participants.1

A silicon mastermind with a silver tongue?

Is it time to replace our ambassadors with machines then?

Maybe not just yet. Indeed, it is not through genius mind games and soft talks that Cicero achieved these results, but rather thanks to a very pragmatic, emotionless playstyle.

To understand it better, let us dive into what makes a good Diplomacy player. The consensus is that to achieve success, one needs to be good in the three following areas:

Tactics - The ability to outplay, outmaneuver, and outguess opponents in direct confrontations. It also includes seizing and anticipating future opportunities in order to gain an advantage on the board.

Strategy - The ability to come up with a coherent winning plan. This means understanding which area of the board to focus on, which alliance should be built or broken, and when to break the status quo to strike with a winning push.

Diplomacy - The ability to create a relationship with other players that will eventually support our strategy, persuade others, cooperate with others, deceive others, and detect their actual intentions.

Additionally, I must add knowledge of the ‘metagame’ is incredibly advantageous. Indeed, despite its open 'bespoke' aspect, Diplomacy is a rigid game. It means there is a 'meta', i.e.: opening theory, stronger countries (Russia is statistically winning fairly more than Austria-Hungary), etc. There are tons of statistics that actually matter, and give a clear edge to the experienced player who is aware of them.2

Cicero has been trained over a 125,261 games data set and is fully aware of those things, so unless it receives very particular sets of messages from other players, it will usually behave by following the statistically 'best' course of action. Hence it already has a very clear edge since many players are just not that knowledgeable and do poor/risky choices from the very beginning. Similarly, there are many situations in the game that are pure tactics and where negotiations play very little role, and Cicero will always perform better than average in those.

Typically, Cicero seems to always play to reach a very flexible position and hardly ever commits too early unless it yields substantial advantages.3 It wants to keep its options open for two reasons:

To be able to make actual use of its tactical prowess, as such a position allows for a large variety of plays.

Because it gives Cicero a much easier time playing the diplomatic game. By staying uncommitted, it sets itself to be the ‘swing player’ that will be solicited by everyone, hence allowing it to choose its best option.

This is why Cicero has a tendency to be very honest most of the time. It does not need to lie in order to reach a favourable position. And once it reaches this position, it can strike with devastating effects due to its tactical strength. The following excerpt from ‘The Game of Diplomacy’ published in 1978 (!) by Richard Sharp is a foreshadowing of Cicero’s playstyle:

“The essence of good play at Diplomacy is to conceal your true intentions, not by telling lies, which simply irritates, but by making ambiguous moves for as long as possible, and striking hard and decisively when the moment arrives. Until that moment comes, make no promises you cannot keep, no threats you may not be able to carry out. If you find that you are consistently able to move as you have said you will move, without suffering any disadvantage, you are playing well.”4

Another fact seems to confirm the idea that tactical super strength is Cicero’s secret. Previous to Cicero’s experiment, the Meta team organised the ‘Meta Speedboat Tournament’. It was an online tournament similar to the BlitzCon Diplomacy Tournament that Cicero entered, with the difference a variant of Diplomacy was used this time: Gunboat.

Gunboat Diplomacy is also called no-press Diplomacy, which means players cannot properly communicate with each other. Their only way to cooperate is to use effective signaling through their moves on the map. Needless to say, this version of the game is way more tactical than traditional Diplomacy, and Diplodocus, the AI that Meta registered for the tournament, absolutely dominated the field. This reinforces the idea that the induction of press Diplomacy hindered Cicero’s performance and that it primarily relies on its raw tactical strength.

Moderating the success - considerations on Cicero’s social skills

To assess Cicero’s performance, it is crucial to note that the tournament it entered was an open tournament. It means anyone could enter, new and experienced players alike. As a result, the field was likely to be affected by an important skill discrepancy between the players, hence making it hard to really assess how strong Cicero is. It is, in fact, quite hard to determine the strength of a random individual at all, since there is not a single unified and densely populated leaderboard as in chess or Starcraft. I am curious to see how Cicero would fare in a closed tournament environment where only experienced players would compete.

It is also important to note that Cicero was artificially filtered so that it becomes a bit more honest and less deceptive and its communication style is very much copied from existing top human Diplomacy players. This is because, during its training over the 40,408 press-Diplomacy games, it was given the transcripts of the in-game discussions. Hence it is not creative at all in that aspect. Copying the style of good Diplomacy players is in fact not very hard to do as long as you have the metagame knowledge to back it up (and as I just described before, it definitely does have this knowledge).

Another feature that facilitated its success, but that is not particularly impressive, is that it has a strong level of commitment. That is to say, Cicero is talking to every player at all times from the very beginning, until the very end.5 This is what a good player should do but not everyone does that because it is quite time and energy-consuming, especially when considering the next point.

Finally, all games were Blitz games, i.e.: with 5min max per turn to negotiate and make one’s moves. This format clearly favours the machine, which can compute way quicker than its human counterparts and amplifies its tactical edge. It also forces people to keep messages small and convey information quickly, which immensely eases Cicero’s job both at interpreting messages it receives and at conveying intents. It seems that it does not fare as well in longer correspondence test games where messages get longer and relationships more complex.

What really impressed me, however, in regard to the diplomatic playstyle of the AI, is how effective it was at signaling intent through its moves rather than through communication. It very often makes some apparently ‘suboptimal’ moves for the sole purpose of conveying peaceful intent. I highly recommend checking out the two examples shown in this video to see how it happens in practice. This is because Cicero/Diplodocus uses a powerful predictive model that computes the most likely intents of its opponents, taking into consideration self-interest, game history, communications, etc…. Making such ‘gestures’, like disbanding a unit close to another player’s borders, or building fleets so as not to alarm a continental power, is not aimed at lowering the guard of this player or at stimulating an emotional response. It is solely aimed at decreasing pressure on this player and increasing the odds they make a more favourable move, i.e.: to start fighting against a common enemy that is rising in power instead of dragging on a fruitless war.6

In fact, the researchers themselves note that it does not take into account the psychological and emotional components of the messages it receives at all. It “does not model how its dialogues might affect the relationship with other players over the long-term course of a game.” Its intentional use of dialogue remains very limited, can at times be exploited, and it still constitutes more of a liability than a strength.

Conclusion: the use of AI in bespoke wargames and the importance of signaling in Strategy

Regarding Cicero's potential legacy with wargaming, I think the fact we can now fine-tune those AIs to impersonate a certain playing style (aggressive, passive, surprising, cooperative, etc) in a relatively convincing way opens up a lot of paths toward new experimentations. In particular, it can make for a good training tool and ‘sparing partner’ to simulate various scenarios. Semantics is definitely not going to be those AIs’ forte just yet, but the fact they are now good enough to be somewhat credible and intelligible is a huge leap forward. I highly doubt their ability to play Matrix games (games with little to no amount of rigid metrics, that are all about arguments and subject matter experts’ adjudication) yet, but it would be really interesting to see how they would fare in other more structured games which have an important ‘open’ negotiation dimension.

Finally, Cicero’s most intriguing feature is not its verbal communication at all, but rather its implicit communication. The way it signals intent, sometimes through ‘shock’ or at first sight ‘suboptimal’ moves, is extremely interesting and is definitely something we need to analyse deeper. The importance of signaling in warfare and geopolitics in general is paramount. This is because Strategy has a strong dialectic component and is always taking place in a multipolar environment. Knowing how to interpret signals and how to convey intent is directly linked to strategic success. Cicero truly excels in this domain and this is what makes it so different from other AIs such as AlphaZero or Libratus. By studying it and taking inspiration from it, we may end up becoming much better at understanding and mastering this aspect of warfare.

Meta Fundamental AI Research Diplomacy Team (FAIR)† et al., Human-level play in the game of Diplomacy by combining language models with strategic reasoning. Science 378,1067-1074(2022). DOI:10.1126/science.ade9097

For more on these stats, see this excellent article by Josh Burton in The Diplomatic Pouch'zine: http://uk.diplom.org/pouch/Zine/F2007R/Burton/statistician3.htm

Full gameplay footage of Cicero with excellent insights and commentaries by expert player ‘DiploStrats’ here.

Sharp, Richard. Chapter 2: “The smyler with the knyf under the cloke” in The Game of Diplomacy. Arthur Baker, 1979. https://diplomacyzines.co.uk/home/contents/the-game-of-diplomacy/

This is notably because, in line with previous AI breakthroughs in other games, Cicero has a very global vision and understands how an action in one corner of the board can have long-term effects on the other side of the board.

Of course, this is also why Meta’s AI was so good at no-press Diplomacy as well. Being able to signal its intents well goes a long way to reach a good diplomatic position.

Super interesting - thanks! Ken