“Strategy requires thought, tactics require observation.”

Max Euwe

Over the last few decades, the widespread use of the term ‘strategy’, in particular in politics, communication, and business, has eroded both the meaning and boundaries attached to it. Nowadays, as noted by Hew Strachan1 or also by Coutau-Bégarie2 and Raymond Aron3 before him, common sense ‘almost does not distinguish a strategy from a policy’4.

Although this abusive use of the word is, in some ways, understandable (after all, strategy seems to be at first sight a broad object, and a very interdisciplinary one on top of that), it should not be taken lightly. Loosely defined, strategy becomes an empty concept, more willingly employed for its prestigious shell rather than its actual substance. Defined too strictly, it becomes a dogmatic tool to enforce a certain system or doctrine rather than a helpful method of thought.

Hence, this article aims to provide a short but neat and comprehensive enough analysis of what strategy means and entails. It reflects my personal understanding of it, although the piece is filled with references to other strategic thinkers that you are invited to explore at your convenience (see footnotes). It is divided in three parts: a definition of strategy, a discussion about its nature as an art or a science, and a dive into its exact purpose.5

Defining strategy

Throughout my readings and studies, I came across many definitions of this term. Sometimes theoreticians, sometimes practitioners, often times both, the thinkers behind these would often frame strategy by putting emphasis on one of its specific attributes:

Its dialectic dimension:

‘The art of the dialectic of two opposing wills using force to resolve their dispute’6 (Beaufre)

The effort ‘to understand your opponent better than he understands you’7 (Charnay)Its heuristic dimension:

‘A struggle for freedom of action’8 (Foch)

‘The art of mastering space and time’9 (Jomini)Its stochastic dimension:

‘The science of action is first and foremost the science of deciding amidst uncertainty’10 (Desportes)

‘Men may second fortune but cannot oppose her; they may develop her designs but cannot defeat them.’11 (Machiavel)

Strategy really is a mixture of all that. My first professor in strategic studies used to say that ‘strategy is calculus if nothing else, the interplay of imagination and probabilities’.12 In the end, taken very neatly, one can say that strategy truly is ‘the art of synthesis’.13 All these different takes led me to progressively build my own definition of strategy, which is the one I will be referring to every time I use this term:

‘The creative combination of all available means and ideas to reach one’s desired end, amidst uncertainty and despite opposing wills.’

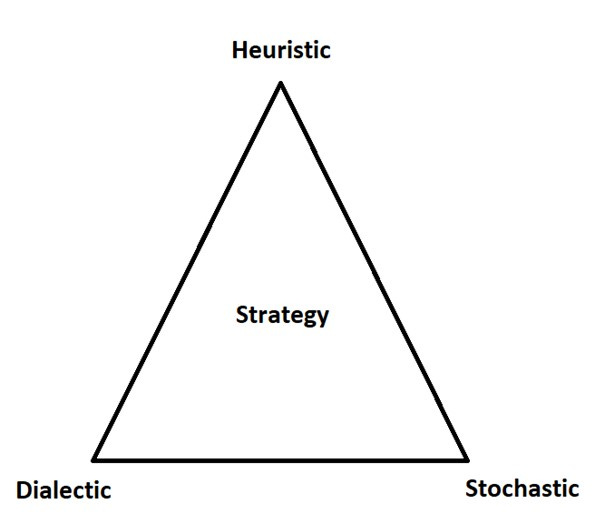

It focuses on the three core dimensions of strategy mentioned earlier on:

Dialectic, that is to say, the opposition of wills resulting in a constant adaptation to each other’s actions.

Heuristic, the imperfect combination of means and ideas used to reach the goal.

Stochastic, the uncertainty and degree of chance involved.

That can best be represented by the following strategic triangle:14

Those three elements form a triangle which cannot be untangled without leaving the realm of strategy. Heuristic and stochastic without dialectic is only mere planning, such as adverse weather preparedness. Stochastic and dialectic without heuristic can be compared to basic card games and gambling involving multiple players. Finally, dialectic and heuristic without stochastic is the confrontation of wills using raw strength or pure calculus, such as arm wrestling or tic-tac-toe.

This triangle is, obviously, a simplified view of what strategy entails, but it is especially useful in order to identify what does and what does not belong to it. It constitutes a middle ground between the Jominian view on strategy, mainly concerned with heuristics, and the Clausewitzian view of it which emphasises the concept of ‘duel’ and the importance of chance.

And what about the military roots of strategy? Isn’t it the science of the general?

I argue this aspect is still kept well alive in this definition. Military strategy accepts organised violence as a means to reach one’s political end, one of the many means that the heuristic dimension of strategy includes. War is an amplifier of all three dimensions of strategy. It maximises everything: opposition of wills, means employed, and hazard. Hence, military strategy takes place when stakes are at the highest and when the use of force is on the horizon. But strategy itself cannot be solely assimilated to it, for there are individuals and organisations engaging in all sorts of non-violent strategic tangles (including all three dimensions of strategy) and using strategic thinking to come on top of these.15

Before moving on to the next part, I believe it is important to introduce a last dimension to strategy, without which this definition would not really be complete: the strategist itself and its singularity.

The strategist, to take a broad definition, can truly be any human being. In fact, according to Kenneth Payne, human beings as a whole have always been strategists. From an evolutionary lens, humans needed strategy in order to ensure survival and fulfil their selfish needs in a competitive environment. And they could effectively resort to strategic thinking thanks to their unique ability to intuit what others think.16 It leads him to see strategy as merely a psychological phenomenon if nothing else.17

Definitely, the singularity of the strategist, including their personality, experience, psychology, culture, imagination, intuition etc, is just as central as the other elements. It permeates every thought and every choice the strategist makes, and sometimes the fight is already won or lost before it even started just because of who the protagonists are. This reality can be transposed to organisations as collective strategising entities, in which their history, strategic culture, tradition, and structure, significantly affect their behaviour. Last, this singularity is also what fundamentally differentiates us from machines and why AIs cannot be strategising entities in the same way we are - this will be the topic of a future article.

Art or Science?

The status of strategy as an art or a science has often been disputed. Why does that matter? Because depending on the perspective taken, both its study and practice are being affected. As I have written in more detail here, it notably affects the production and assimilation of principles and doctrines.18 There is a tension between the tempting will to assign rules and principles to war as a phenomenon, which can be reassuring, and the practical reality that tends to show that ‘no plan ever survives first contact with the enemy’.

Strategy, by nature, is always contextual. It is entirely dependent on the context and the project it serves. Hence, strategy comes closer to ‘a method of thinking’, since its volatility and the absence of a clear set of laws or principles associated with it hardly makes it a science. Rather, it can only be ‘a science of accident’, according to the Aristotelian sense of the term19, or ‘a theory of action’. It is perhaps best understood as an art, for it uses ‘similar cognitive abilities’, namely imagination and improvisation, and is ‘nested in a social context while aiming simultaneously to shape this context’.20

But if the conduct of strategy is an art, its study can be considered a science. Indeed, to the external observer that aims to understand the dynamics of conflict and decision-making, this art takes place under clearly identifiable constraints. For instance, the concept of the strategic triangle is a theory that aims at identifying those universal constraints that affect the strategist. Hence, strategy, as a field of academic study, is a theory of action that constantly deals with specific contexts and attempts to understand how those variations of context and constraints affect the strategist’s decision-making.

Consequently, the study of strategy is inherently highly empirical, and theories can only be refined by experience. Napoleon never formally wrote a ‘guide’ to strategy, but he always encompassed the importance of bon sens (judgement) and imagination (creativity): to be able to assess the options you and your opponent have, and have enough imagination to figure out how to unexpectedly recombine these options and figure out new ones. Becoming better in that sphere can only truly be achieved through experience.

Hence, becoming a better strategist means experimenting, and it means doing mistakes. This substack puts an emphasis on wargaming specifically for this reason. In times of peace, it is a great way to practice in an environment where mistakes cost nothing, except for a bit of pride when one is losing a game. But even more abstract games, such as chess, help you improve these strategic abilities. Chess is a game in which you can play 40 excellent moves, but a single bad decision on the 41st move can make you lose the game. Chess is a cruel game, and it can absolutely crush one’s ego. Yet, it teaches a lot about one’s limits and humility. Indeed, a great player ‘knows he’s always one move away from losing the game, and that’s exactly what keeps him from losing’. It is this humility that enables him to be audacious, but prevents him from being reckless. Yet, it can only be acquired from practice and experience. Strategy games, martial arts, and some sports offer insights into strategic thinking, but truly any experience in a competitive environment can be valuable in that regard.

Nonetheless, practice alone is not enough - it also requires reflection. It requires an understanding of what worked, or what did not work, and for which reason. Hence, strategic theory and strategic practice are always subject to continual refinement as they feed each other.

A sense of purpose: levels of strategy and freedom

But why strategy? Why does studying and practising it matter? Where does it take place in the grand scheme of things?

While the discussion so far has focused on what strategy exactly entails, its definition would not be complete without a deeper look at what it is for. The definition I use simply states that it is used to reach “one’s desired end”, and while this formulation is loose enough to account for the ubiquitous character of strategy, it nonetheless hides the deeper nature of the links intertwining strategy with its purpose.

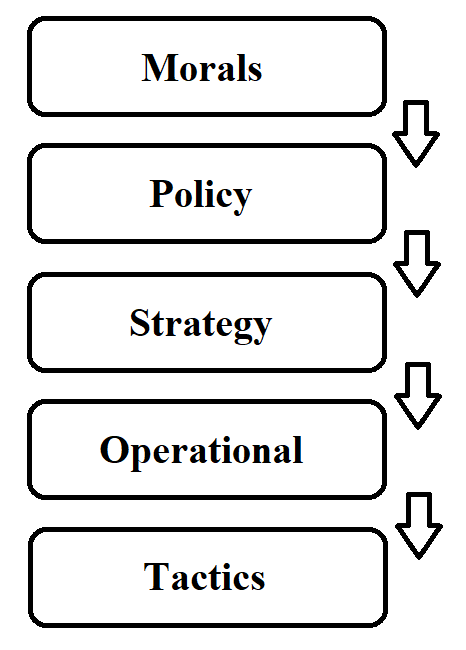

Indeed, on this topic first comes to mind Clausewitz and his definition of strategy as a political instrument, whose purpose is to guide war to achieve political objectives.21 It allows us to differentiate the goals ‘of war’ and ‘in war’. The classic pyramid of the levels of war goes: Policy > Strategy > Operational > Tactics.

Here I want to expand a bit on this topic by putting emphasis on the importance to include morals at the top of this pyramid.

Why does it matter? Because policy, by nature, can rarely be fully and strictly determined by fixed objectives and numbers to attain. Rather, it is loose and volatile, and can be defined as ‘the general principles which guide the making of laws, administration, and executive acts of government in domestic and international affairs’.22 It is generated and justified by values, beliefs, and philosophy, all encompassed by the morals category in this pyramid.

Yes, sometimes the conduct of policy may require going against some of these ethical guidelines, but these cases shall remain exceptions to the rules. As the character of Thomas More in A Man for All Seasons frames it: “when statesmen forsake their own private conscience for the sake of their civil duties, they lead their country by a short route to chaos”.23

The intangible character of policy has a very direct consequence on strategy: because policy alone is not always enough of a guidance, strategy is directly linked and subordinated to morals, and morals continually permeate its conduct. Just like the ‘spirit of the law’ dominates the ‘letter of the law’, the ‘spirit of policy’ dominates the ‘letter of policy’. The perceived intention behind policy, and the morals, values, and philosophical ideals overarching it are what strategy ultimately strives to achieve. A successful strategy brings a nation closer to these ideals than it was before.

While this idea applies to political institutions, it becomes even clearer when we adapt this pyramid of strategy to the individual. Here, the concept of policy can be replaced by a long-term vision, a particular perception of the future that the strategist ought to achieve. This perception is, again, generated by a set of moral values and a specific system of thought.

And from this short analysis finally emerges the true purpose of strategy: to enable freedom. It allows those who study and practice it, nations as well as individuals, to maximise their chance to be free to pursue whichever future they want for themselves. ‘A way to not be at the complete mercy of events and randomness’24 (Desportes).

In that sense, it is more than just ‘a struggle for freedom of action’ (Foch). Strategy aims to gain freedom of action in order to ensure freedom of will. This is how I understand the definition given by Lawrence Freedman, who broadly defines strategy as ‘the art of creating power’.25 Indeed, a good strategy does not simply beat your opponent. It is supposed to bring you closer to your ideals. If you succeeded at the latter, it means you actually created power. This is an important nuance to grasp, good strategy is not defeating your enemy, it is getting closer to your absolute goals.

There would be many interesting digressions to explore from that point, such as the meaning of strategy and competition in society, since strategy always enables freedom at the expense of someone else’s freedom. Or the idea that the result in war is never final, since conflict starts in the mind, and strategy cannot eternally repress dissent.26 What about the biological roots of strategy, can neuroscience and the study of the brain help us become more competent strategists? We saw that strategy is deeply linked to morals and psychology, yet, can a non-self-aware AI be an efficient strategist? Is there such a thing as a philosophy of strategy?27 All these topics will be the object of further articles. For one thing, they illustrate how interdisciplinary the study of strategy is, and how much more there is to be thought and written about it.

Finally, a last note must be addressed to the reflective effect of strategy. Morals are refined by thought and experience. As the strategist attempts to shape the landscape around them, and as they attempt to shape their future, their views are constantly challenged and their perspective on the world evolves. Doing strategy also requires constant confrontation within the self as well as deep introspection, not only to precisely know what exactly you are trying to achieve but also to understand your strengths and weaknesses and thus be effective in the struggle to come. Last, you paradoxically learn a lot about yourself thanks to your foes. Strategy forces you to put yourself in your opponent’s skin and understand how he thinks. Fighting a stranger over a ring or a chessboard leaves you with a strange and unique relationship with this person. You don’t know each other, but you both had to put all your mental strength in trying to understand each other nonetheless.

This is, I think, the main reason why I am attracted to strategy, both its study and practice. Conflict and competition expose both human ingeniosity and fallibility. It inevitably builds character. In any case, whether you achieve your goals or not, it always makes you grow.28

Strachan, Hew. « The Lost Meaning of Strategy », Survival, 2005

Coutau-Bégarie, H. « Traité de stratégie », Paris, Economica, coll.« Bibliothèque stratégique », 2011 (first published 1999)

Aron, Raymond. “Remarques Sur L'évolution De La Pensée Stratégique (1945-1968): Ascension Et Déclin De L'analyse Stratégique.” European Journal of Sociology, vol. 9, no. 2, 1968, pp. 151–179.

Vennesson, P. « Chapitre 29. La stratégie », Thierry Balzacq éd., Traité de relations internationales. Presses de Sciences Po, 2013, pp. 717-746.

Some parts of this article are directly extracted from my Master’s Thesis completed at King’s College London, “How can Artificial Intelligence provide insights to modern strategic thought? Using wargames as a bridge between machines and strategists”, 2022.

Beaufre, Andre. “An Introduction to Strategy: With Particular Reference to Problems of Defense, Politics, Economics, and Diplomacy in the Nuclear Age”. New York: Praeger, 1965.

Charnay, J.-P., “Essai général de stratégie”, Paris, Editions Champ Libre, 1973, p. 19.

Foch, F. “Des principes de la guerre”. Economica, coll. « Bibliothèque stratégique », 2007, p.95

Jomini, Antoine H, George H. Mendell, and Wm P. Craighill. “The Art of War”. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co, 1863

Desportes, Vincent. « Inflexions : exception et incertitude », Inflexions, vol. 4, no. 3, 2006, pp. 193-198.

Machiavelli, N. The Discourses, Book II, p.383 in “The Prince and The Discourses”. New York: Modern Library, 1950.

I would like to acknowledge Étienne de Durand who was my first teacher in strategic studies at Sciences Po Paris.

Desportes; Vincent. “La Guerre probable : Penser autrement”, Paris, Economica, coll.« Stratégies et Doctrines », 2007

The concept of strategic triangle such as exposed here was first introduced by Quentin Censier. For French speakers, see : Censier, Quentin “Wargame et méthode : Jouer la guerre pour mieux la comprendre - Sur le Champ.” YouTube, 10 Dec. 2020

Levine, R., Schelling, T., and Jones, W. "Crisis games 27 years later: Plus c'est deja vu." Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. 1991

Barkow, Cosmides, Tooby. The Adapted Mind : Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992

Payne, Kenneth. “Strategy, Evolution, and War : From Apes to Artificial Intelligence”, Georgetown University Press, 2018

Alloui-Cros, B. “What is the Utility of the Principles of War?”, Military Strategy Magazine, Volume 8, Issue 1, summer 2022, pages 42-46

Aristotle, “The Eudemian Ethics”, translated by Anthony Kenny, Oxford, 2011

Payne, Kenneth. “Strategy, Evolution, and War : From Apes to Artificial Intelligence”, Georgetown University Press, 2018

Clausewitz, Carl , Michael Howard, Peter Paret, and Bernard Brodie. “On War”. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1984.

As defined in: Scruton, R. “The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Political Thought”, Third Edition, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, p.529

Zinnemann, Fred. “A Man for All Seasons”. 1966.

Desportes, V. “Entrer en stratégie”, Robert Laffont, 2019.

Freedman, Lawrence. “Strategy”. Oxford University Press, 2013.

For readers interested in this topic, I invite them to read M.L.R. Smith, “Quantum Strategy: The Interior World of War”, Military Strategy Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 1 (2012)

I would like to acknowledge Dr. Julien Durand de Sanctis, who has been teaching an excellent class on “Philosophy of Strategy” at Sciences Po Paris.

To have more concrete examples and insights on this topic, I cannot recommend enough the excellent Art of Learning by Josh Waitzkin: Waitzkin, Josh. “The Art of Learning: A Journey in the Pursuit of Excellence”. New York: Free Press, 2007.